Loop Hero is turning role-playing games on their head and it has a long rich tradition in the gaming industry.

Titles like Majesty: The Fantasy Kingdom Sim and its revamped sequel showed more than 20 years ago just how fun and in-depth it is to play with classic fantasy hero archetypes without having any ability to directly control them. On the outside, this lack of direct manipulation ability might feel like it is moving RPG gameplay more to the realm of simulations or even strategies.

However, thanks to some smart game design moves, these atypical RPGs continued to appear, offering an experience that is neither classical role-playing in line with the D&D setup nor a reskinned management sim.

Instead, games of this type aimed to offer their custom blend of experiences that is hard to define, but easy to recognize once all of the ingredients stick together in the right way.

How did Studio Four pull this off?

Studio Four Quarters pulled this off - to a degree - with their Loop Hero. This release from 2021 simply calls itself a roguelike game, but I’d argue that it perfectly fits into the wider notion of games like Majesty.

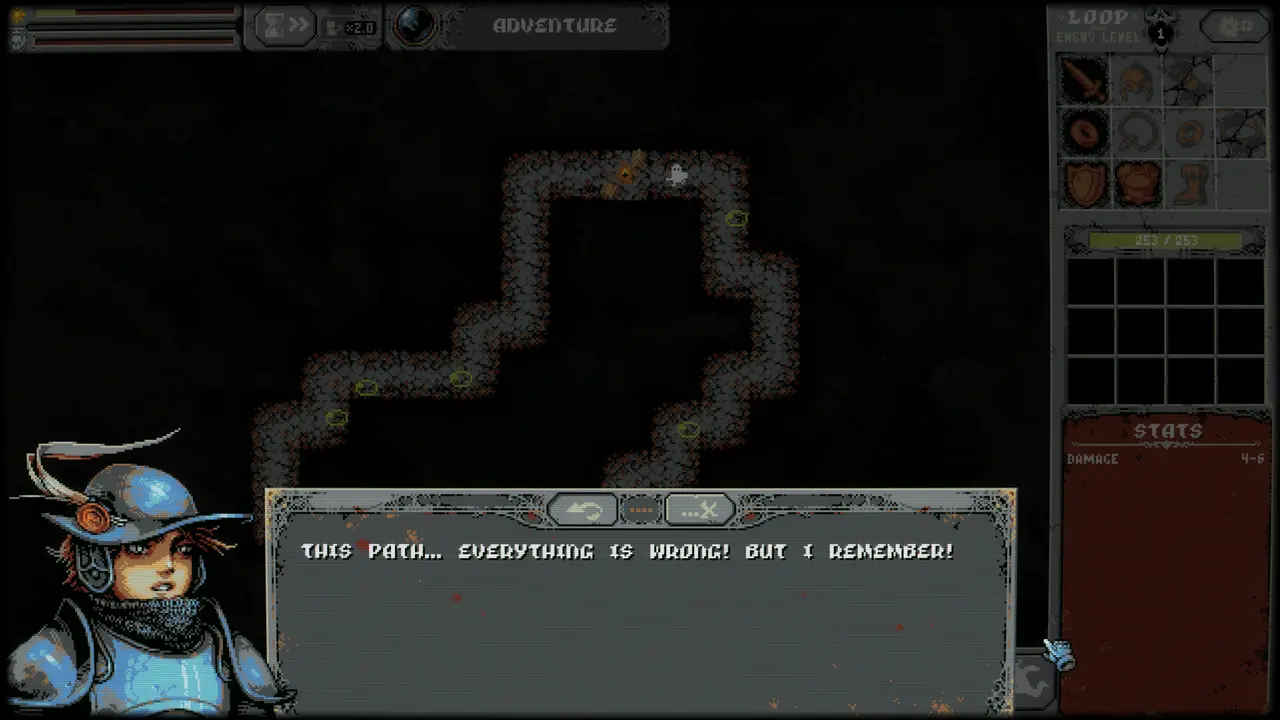

In the game, the players are greeted by a world that has nothing in it - literally. The game and its unnamed hero protagonist enter a world that is no more. In it, a lich destroyed reality itself and all that is left is empty space. Unswayed by these enormous existential obstacles, the hero simply awakens and begins to walk a path in the emptiness - the path goes round and round but loops back into itself. On this path, however, the long road of danger, combat, discovery, and rebuilding begins.

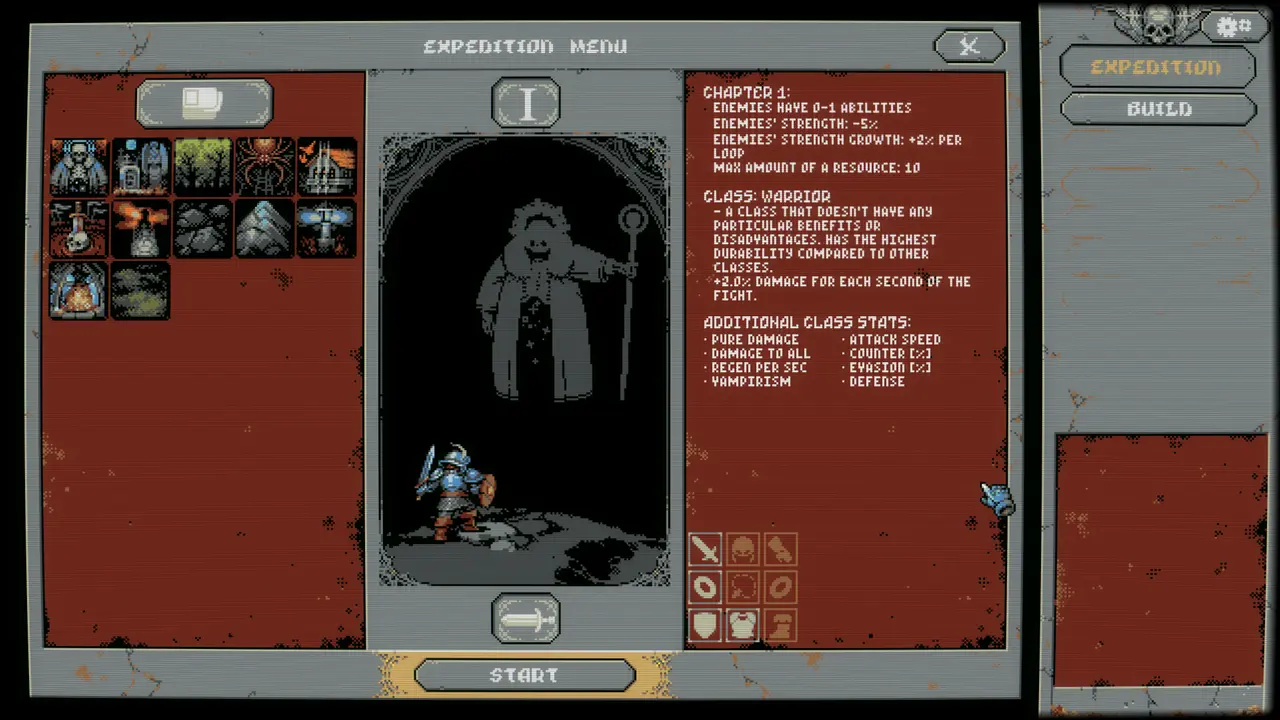

Character Selection

The players have no control of their hero character, but instead, use a card-based system of building and creating things around the same path. Each path the player takes equates to a run. On the same run, the hero functions as a regular RPG character - they have their stats, gear, spells, and other stapes of fantasy action that can help them on their journey.

As the player builds, they add both challenges and benefits to the hero. For example, a graveyard card will spawn undead enemies, while fields will help towns but will spawn deadly scarecrows.

The players are able to build both on the loop, but also around it, adding meadows, hills, mountains, and many other features of landscape, all the while as their hero continues to walk the path and take on everything and anything on it.

Pixel Art graphics, designed to look like upscaled visuals from the late 1980s games, fit great into this void-like universe. As the players progress through the runs, they slowly build up their run-world from a simple loop on a black background to a lush fantasy world with its safe corners, dangerous stretches, and many other elements that easily grow on the player, regardless of the fact that runs rarely take longer than 20 to 30 minutes, including all auto-combat matches.

More on the gameplay

Yet, each of them feels unique, and each beckons the player to get invested, one building card at a time. At the end of the run, the hero takes on the boss and regardless of their success or failure, the new loop and run await after that.

The concept, no matter how simple it might sound, takes some getting used to. Like many other inverted RPGs, some things in Loop Hero are completely straightforward and others obscure to a point of prolonged unclarity. The same goes for the metagame between the runs, where the hero builds the base camp with different upgrades and new buildings.

This is completely separate from the runs themselves and fits into the roguelike setup. However, the process of building the base camp and the different options that slowly become available remain only partially clear even after hours of gameplay.

It is hard to figure out if some issues here arise with the language localization of the game or the original language of the developers (a studio based in Russia) or through a dedicated approach of making the players work through many dilemmas by crude trial and error.

That metagame problem is the ultimate issue of Loop Hero. While it runs itself and is clear and fun, the wider game, just like the odd narrative where players take the lich and defeat it time and time again - without anything changing - is a difficult pill to swallow. Outside of the loop runs, I always felt like I got 85% of things I should get and I’m certain that I’m not alone in that feeling.

Because of that void (pun intended) of understanding and a persistent lack of total, game-wide clarity, Loop Hero is a release that many will enjoy immensely when they first try it out, but which will play until its very end.